Industry innovator and WWII vet

Since Indiana Tech’s founding in 1930, we have striven to prepare our students to be the leaders of tomorrow and motivate them toward lives of significance and worth. That is—and always will be—the Warrior Way. Learn about Howard “Mack” Turner, an Indiana Tech alum, who benefitted from the Warrior Way and lived a life of significance and worth. The next time you twist open a 2-liter bottle of ice-cold Coca-Cola, take in that first deep drink and bask in the satisfaction of its perfect effervescence, give thanks to Howard Turner. It’s because of his work decades ago that your favorite carbonated soft drink has that snap you crave and the plastic bottles they come in look the way they do. Howard, a dual-degree alum of Indiana Tech, was an innovator in the plastic bottle industry at a time when the use of plastics to create everyday products was proliferating worldwide. However, creating the perfect plastic bottle to satisfy the needs of the carbonated beverage industry was far more involved than one might think. The wall of the bottle needed to be thick enough to prevent the escape of carbon dioxide, the gas that gives soft drinks their fizz. It also needed to be designed to mitigate a phenomenon called creep—an escape of carbon dioxide from the beverage into the empty space between liquid and cap that also results in flat pop. In addition, they needed to withstand the rigors of transport to market and maintain an acceptable shelf life once there.

Greg Turner provided a side-by-side comparison of a current soft drink bottle next to a prototype created by his father’s team back in the sixties.

“Today in 2020, if you buy a 2-liter bottle of Coke and look at the plastic green bottle from my childhood, you will see the same basic design in appearance in the ‘footings’ of both bottles.”

“Back in the mid-1960s, periodically on weekends I would go with him to the Continental Can Plant, which was located on West 59th in Chicago,” said Dr. Greg Turner, the first of five children born to Howard, and his wife of 58 years, Rita Catherine. “I recall vividly seeing him and his extruder technicians working on and producing various prototypes of bottles. I overheard many conversations between him and the technicians about the design, shape, bottom footings and, more importantly, ways the bottle could be perfected to maintain effervescence and eliminate CO2 creep.”

For Howard, who passed away at age 95 on Feb. 20, 2020, at his home in Mokena, Ill., helping design, perfect and patent that plastic Coke bottle was his proudest professional accomplishment. However, it was merely one of a lifetime of triumphs for Howard.

Born in 1924 on a family farm in Fort Blackmore, Virginia, Howard and his four siblings faced humble beginnings in their rural farming community. As was the custom of the day, the Turner children had significant roles in keeping the farm operating. It was common for Howard to tend to morning chores, walk several miles to attend school for the day, and then return home for more evening chores.

“It took courage, determination, an indefatigable vision and unwavering faith in God’s love to rise from those humble beginnings,” Greg said.

As a member of the 38th Cavalry, he was on the first tank to liberate Paris. A year later, he served on General Dwight Eisenhower’s staff that prepared the Act of Military Surrender, which was signed by Nazi Germany’s High Command early in May 1945 and ended World War II in Europe. Howard departed from the military as a Corporal 1st Class in December 1945.

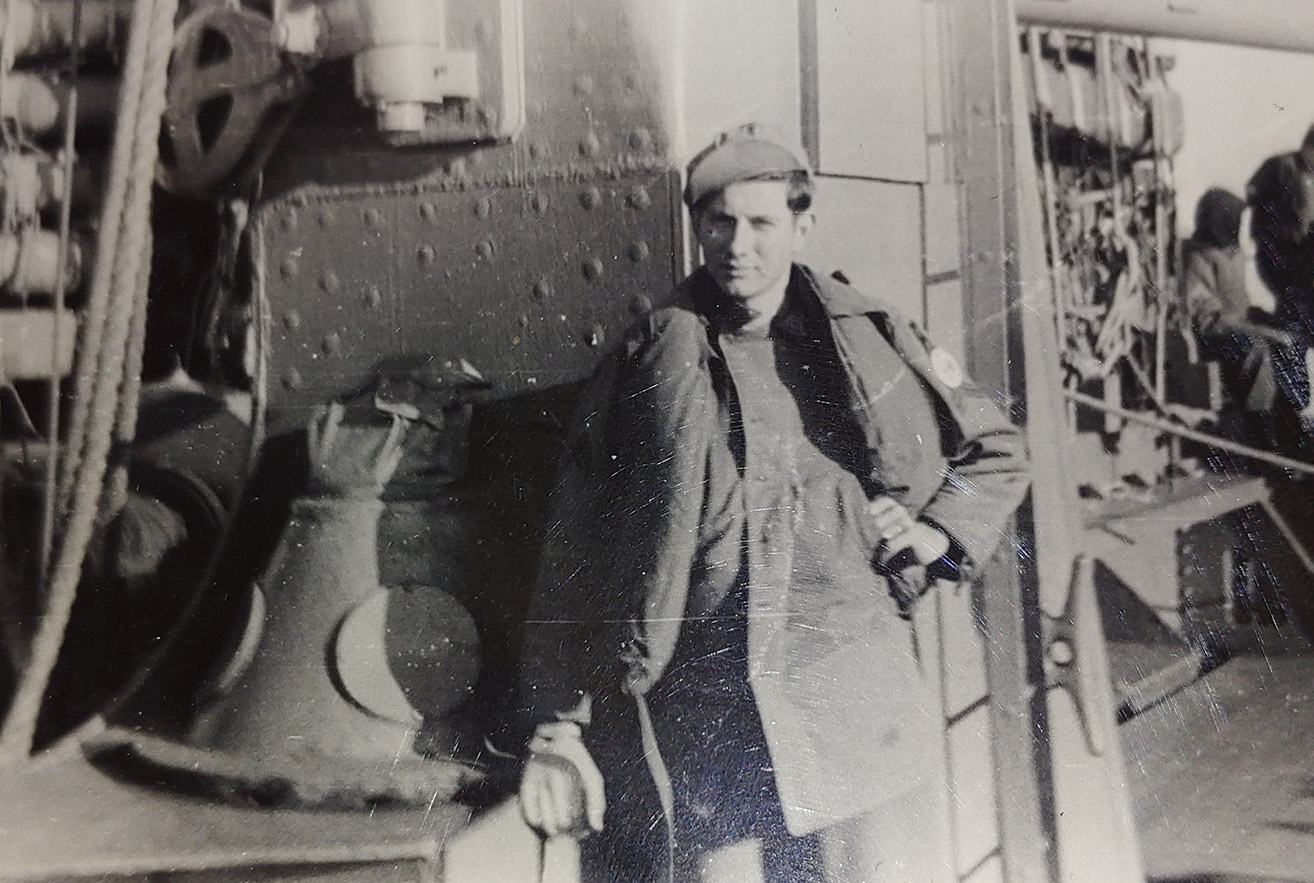

Following his older brother’s footsteps and a patriotic urge, Howard joined the Army in 1942. In August 1944, as a member of the 38th Cavalry, he was on the first tank to liberate Paris. A year later, he served on General Dwight Eisenhower’s staff that prepared the Act of Military Surrender, which was signed by Nazi Germany’s High Command early in May 1945 and ended World War II in Europe. Howard departed from the military as a Corporal 1st Class in December 1945.

“He described a few times the suffering and horror he saw and experienced, but he was stoic about his service record,” Greg said. “He would merely say he did his duty and was proud to have served his country to the best of his abilities.”

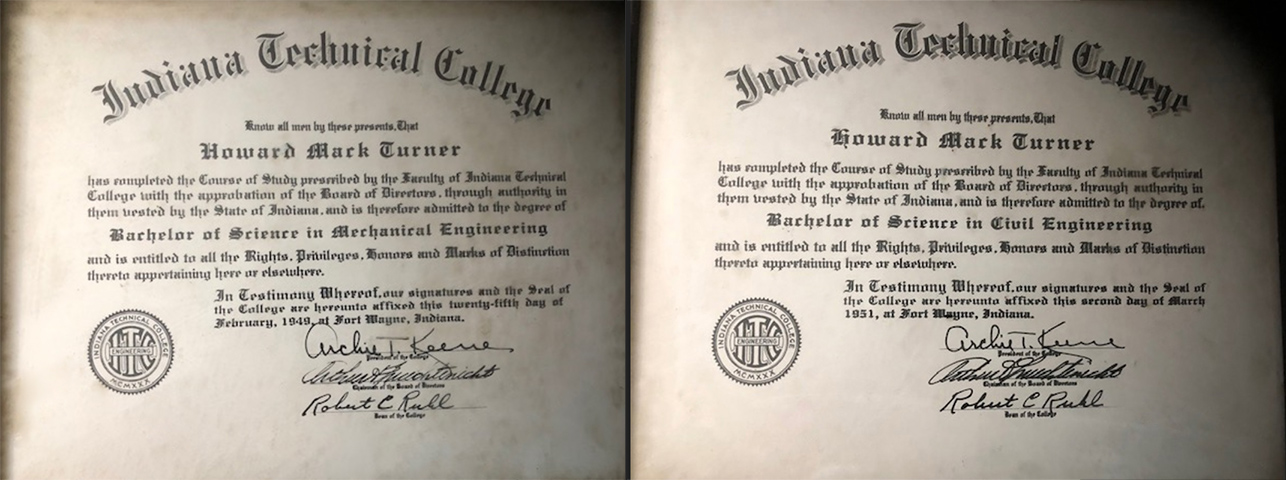

After being discharged from the Army, Howard took a tip from one of his army buddies—a guy from Fort Wayne who recommended an engineering school there called Indiana Technical College. Howard took a chance on the school, and by the end of the decade, he had earned two degrees—one in civil engineering and the other in mechanical engineering. He had also laid the foundation for an outstanding career.

“He was proud of his alma mater; in his home offices, he always hung his diplomas proudly on the wall. He recognized that the education he received at Indiana Tech prepared him well for his professional career in the plastics industry,” Greg said. “After he graduated, my father attended several class reunions and our family has maintained its affinity toward Fort Wayne with many visits to extended family members who still reside in the city.”

Howard worked at U.S. Rubber Co. in Fort Wayne from 1950-1960 before beginning a long relationship with Continental Can Co./Group. At Continental, he was the general manager of plastics technology from 1960 to 1977 and from 1987 until his retirement in 1996. From 1977 to 1987, he was vice president of research and engineering at Ludlow Papers and Flexible Packaging in Mt. Vernon, Ohio.

In addition to his groundbreaking work on plastic bottles for the soft drink industry, Howard and his teams also worked with NASA on plastic food containers and delivery methods, as well as rocket cabin fire extinguishers. At the time of his retirement, more than 100 U.S. government technology-related patents were credited to him.

The choice to take a chance on Indiana Technical College also led Howard to his wife, Rita Catherine. They met through mutual friends and, in 1950, began a 58-year marriage that produced five children. Greg is an associate professor of behavior sciences and social medicine and associate dean for faculty development at the Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee, Fla. He has a brother who is a home care nurse and another who is a K-12 teacher and department chair. One of his sisters is retired from the supermarket industry; the other is deceased. Rita Catherine passed away in 2008.

When asked what life lessons Howard instilled in his children, Greg replied, “Life-long learning, hard work, dedication and commitment, resilience, love of this country, understanding and patience, among others.

“He once told me, ‘To teach a man how he may learn to grow independently, and for himself, is perhaps the greatest service that one man can do for another.’ That best captures his philosophy, his leadership behavior and his parenting practices he used in raising five children. Perhaps due, in part, to a life of challenges, dedication and diligence, self-sacrifice and hard knocks, he could be demanding at times. I always believed growing up, and the rare times I saw his demanding side, it was due to his setting high expectations for himself and those he cared about.”

When time would allow, Howard would satisfy his deep passion for flying. He earned a private pilot’s license in 1963 and completed instrument rating certification in 1968. That certification is one a pilot—private or commercial—must have in order to fly cross-country and at night. It requires specific intensive training, instruction and the completions of standardized written and performance examinations beyond what is required for a private pilot certificate.

“He was prodigious in many ways. Although, being a humble man, he never considered himself a striking success,” Greg said. “In fact, if he were alive today, I doubt very much that he would approve of my being a troubadour of his WW II experiences or his professional accomplishments.”

The Warrior Nation is glad you did.

This story was written by Matt Bair, director of marketing and communication for Indiana Tech, in collaboration with Dr. Greg Turner, the eldest child of Howard Turner’s. Dr. Turner is an associate professor of behavior sciences and social medicine and associate dean for faculty development at the Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee, Fla.